Mennonite Furniture vs. Amish Furniture

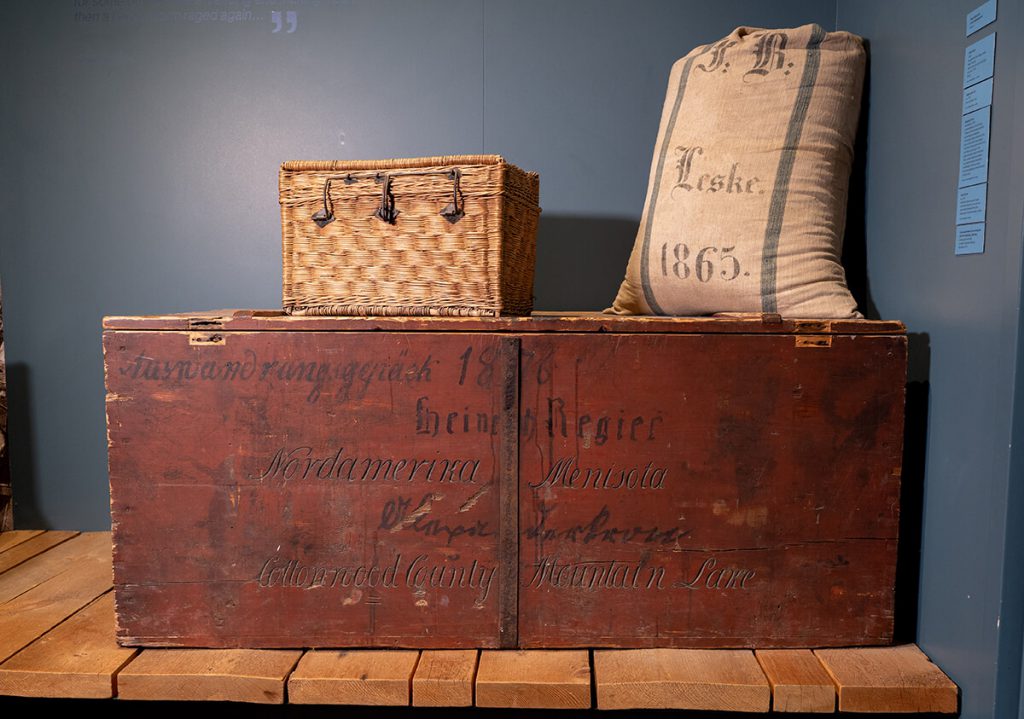

They wanted to follow Jesus in their own way and refused to serve in the military. They sought a life separate from the culture where they lived in order to speak their own language and continue their way of life. And they were persecuted, imprisoned, and fined. They sold their land, uprooted their communities, and found new homes. But when they discovered that no place in Europe was safe, they packed all their belongings into trunks, boarded ships, and traveled across the ocean to a new life…a life in America.

This is the story of the Amish, but also the story of the Mennonites: two parallel journeys of faith, hope, and discovery. More scholarly people than I can tell the full history of these groups, but today I will share just a glimpse into the Mennonites’ journey to America through the furniture they brought with them.

Immigrating to America

The large, wooden chests that these Mennonite immigrants brought with them to carry their belongings were made of solid wood, crafted with dovetailed joints, and occasionally adorned with decorative artwork. Sometimes, their destination in America was printed right on the wood. How do I know this? Because I recently had the opportunity to see some of these chests, approximately 150 years after they were built.

Who are these Mennonite immigrants?

With roots in Poland’s Vistula Delta, this cultural-historical tradition is different from Pennsylvania German Mennonites and Amish which originated in Switzerland and south Germany.

Though they’re sometimes called “Russian Mennonites,” the group featured in this exhibit weren’t ethnically Russian at all. Before setting out for the United States, his group moved East to the Vistula Delta region of modern-day Poland, Ukraine, and Russia. In that region, they attempted to maintain their independent language, culture, and religious beliefs.

While many Amish communities and other Mennonite communities left Switzerland and Germany in the early 18th and 19th centuries to settle in the Eastern and Midwestern United States, these “Vistula Delta Mennonites” immigrated to America much later. Between the 1870s and 1930s, when this group came over, they ventured further west, settling in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.^1

A Mennonite Furniture Collection

Today, nestled in the heart of the great plains of central Kansas, you can find a wide, brick building that houses the Kauffman Museum. This unique museum sits on the campus of the Mennonite-affiliated Bethel College in North Newton, Kansas. It serves to foster learning experiences to help us reflect on the people and the natural environment of the central prairies, with emphasis on the story of the Mennonites. It was here that I viewed the largest collection of Mennonite immigrant furniture, nearly all built between 1870 and 1910.

Characteristics of Mennonite Furniture

Every chest, wardrobe, and day bed in the exhibit is different. They were built in the days before mass manufacturing. Some were brought from Europe; others were built here in their new home after the move. But all were hand-built by Mennonite immigrants using construction techniques they learned in their communities.

Comparing Antique Mennonite Furniture to Amish Furniture Today

So, what can we learn about the furniture made by Mennonites when they left Eastern Europe around the 1870s and 1880s? Well, they’re remarkably similar to the furniture that many Mennonite and Amish woodworkers continue to build today!

Inside the Dowry Chests

These chests were made of solid wood and far too large for one person to carry alone. They often featured a shelf in the back, a lidded side compartment known as a “till” against one wall, and a large open space to pack larger items. Most were fashioned with a metal latch and lock. Hope chests and trunks made today are generally smaller with wide-open interiors or removable trays.

Dovetailed Joints

Dovetailed corners were a popular joinery technique among Mennonite craftspeople, displayed prominently in this chest pictured. They are still used today for drawer boxes in storage pieces and in hope chests.

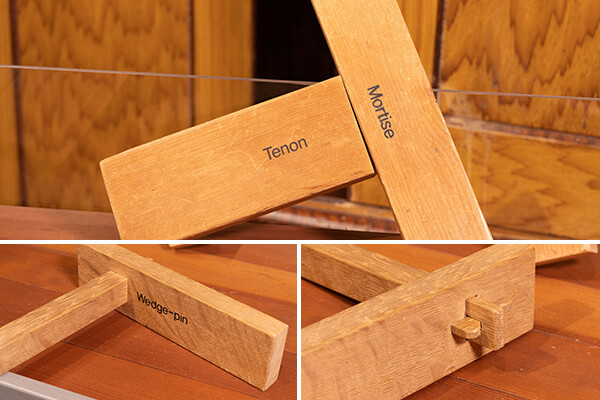

Mortise and Tenon Joints

Various forms of Mortise and Tenon connections were used, including some with a wedge-pin locking the tenon in place. Mortise and Tenon construction is characteristic of Mission style furniture.

Wood Inlays

Several of the more decorative pieces feature wood inlays made of a different wood type and set into the top or front of the piece. This is a technique used in Amish pieces today, sometimes with ebony wood inlays.

Decorative Moulding

A few wardrobes feature moulding on the top, a decorative technique still offered today.

20-Piece Wardrobes

Perhaps the most surprising thing I found was that these Mennonite immigrants could disassemble their wardrobes! Some wardrobes can be broken down into more than 20 pieces, all without removing any nails or fasteners. To accomplish this, they often relied on dovetail cleats that hold fast when assembled but slide apart to release the connection when the piece needs to be moved. Unfortunately, we don’t know of any Amish wardrobes that use this technique today.

Veneers on Mennonite Furniture? Sort of.

Mennonite immigrants were skilled and knew how to make the most of their materials. Though some pieces of furniture were made with hardwoods like oak and ash, others were crafted with more common woods like pine and poplar. Though Amish woodworkers do not rely on veneers or laminates today, these Mennonite woodworkers often did (in a sense), using rollers and brushes to paint or stamp faux grain patterns on the wood. This primitive veneer was a popular method at the time to dress up a lower-cost piece of lumber. You can find out more about these techniques and much more in Reinhild Kauenhoven Janzen and John M. Janzen’s book Mennonite Furniture: A Migrant Tradition (1766-1910).^2

Unfortunately, within a generation of their emigration to the U.S., this furniture-making tradition had largely died out due to the expansion of mass-manufactured furniture in America.

How Can You Preserve Your Family Heirloom Furniture?

Well, it all starts with the initial build quality. Kauffman Museum’s Collections Coordinator Dave Kreider told us, “Furniture that’s handmade is going to have more value and hold up. They use authentic materials and techniques. These [in the exhibit] are all real wood and use traditional joinery methods.” So, if you’d like to have something that will last, avoid veneers, laminates, and manufactured wood products.

Even with well-made furniture, you should take good care of it if you’d like it to last for more than a century. Kreider continued, “In terms of preserving furniture, temperature, light, and humidity are the biggest factors. And stable humidity is probably the biggest factor. Get it out of the moist basement.” To learn more about protecting heirloom-quality wood furniture, click the link to view our Caring for Wood Furniture page.

Kauffman Museum’s Collection Today

Kauffman Museum’s collection now includes over 50 pieces of furniture. Along with the largest collection of original Mennonite immigrant furniture, you’ll find stories of the immigrants’ history, interactive samples of the joinery techniques, and a seven-minute video titled The Waning of the Tradition. The collection continues to grow, primarily through donations of family heirlooms from Mennonites in Kansas. The furniture is cleaned and protected by the staff at the museum before being considered for display in the exhibit hall.

The Mennonite Immigrant Furniture exhibit is just one of Kauffman Museum’s exhibits about Mennonite settlers and life on the plains. Learn more at kauffmanmuseum.org, and if you’re in the area, schedule a trip to see it for yourself.

Parallel Traditions: Amish and Mennonites

Today, Amish and Mennonite people in America dress differently from one another, hold quite different stances on the use of technology, and orient their families and culture around different social structures. But the persecution and hardships that drove them across the ocean to pursue religious freedom were very similar. And their new lives in America were only possible because of the skills and traits they brought with them from Europe.

In some ways, it’s the most traditional American story there is: seeking a new life and freedoms in “the new world” and building it for themselves…one board at a time, one stroke of the saw at a time, and one swing of the hammer at a time. Amish woodworkers are still doing the same thing today, building a legacy with their heirloom-quality furniture that may wind up in a museum centuries from now.

^1 Kaufman, Edmund G. (1973), General Conference Mennonite Pioneers, Bethel College, North Newton, Kansas.

Smith, C. Henry (1981) Smith’s Story of the Mennonites. Newton, Kansas: Faith and Life Press. pp. 249–356. ISBN 0-87303-069-9.)

^2 Janzen, Reinhild Kauenhoven and John M. Janzen. (1991), Mennonite Furniture: A Migrant Tradition (1766-1910). Intercourse, Pennsylvania: Good Books.

Jake Smucker grew up attending a Mennonite church while living on a small farm in central Kansas. After studying at Goshen College in Elkhart County, Indiana, he started working for DutchCrafters in 2016. Since then, he has been the Multimedia Producer and Graphic Designer, focusing his efforts on producing helpful and informative videos for shoppers of Amish furniture.

Well researched and written. Good use of historical artifacts close to home. The photos are great. The author was obviously well raised.

Thanks for showing the differences between Mennonite furniture and Amish furniture with detailed information.