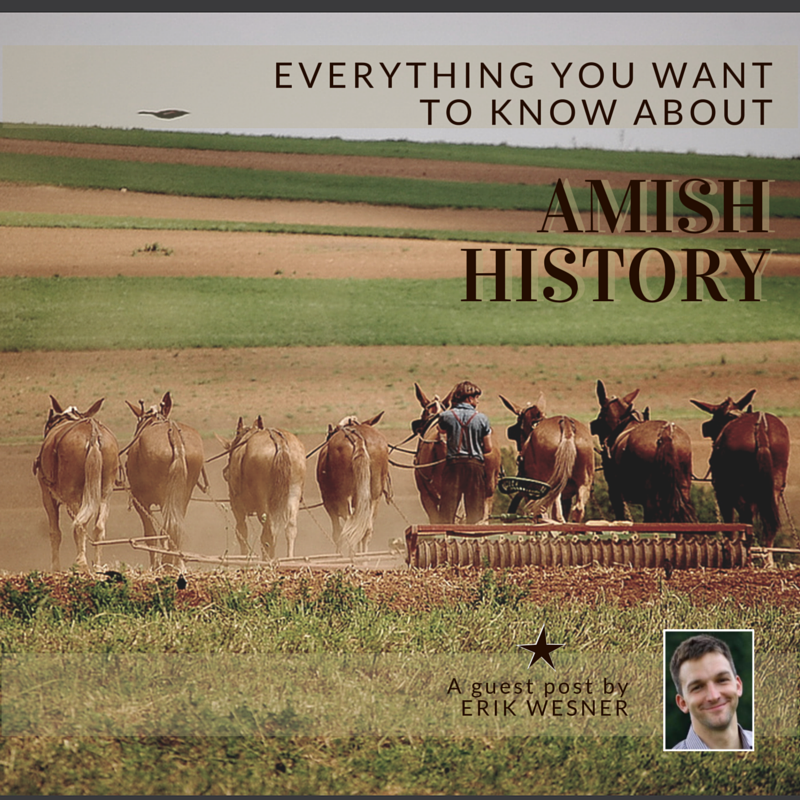

Everything You Want to Know About: Amish History

Amish History

By Erik Wesner, author of Success Made Simple: An Inside Look at Why Amish Businesses Thrive,

Where do the Amish come from? How did they find their way from Europe to America? We take a brief look at Amish history below, dating back to their roots in 16th-century Europe.

Anabaptist Beginnings

In the first decades of the 1500s, religious reformers in Europe began to challenge the Catholic church, balking at certain practices and mores of the state institution. Against the backdrop of the Protestant Reformation, a group of Swiss radicals spearheaded their own movement, objecting to a number of church and state strictures, including infant baptism, military service, and the swearing of oaths.

The original split seems to stem from the “rebaptism” of adults by a group of religious radicals in 1525.

Tensions came to a head in 1525 when a group of radicals met in Zurich, Switzerland and re-baptized one another, a sign of their belief that baptism should only be performed on consenting adults. They were given the derogatory name “Anabaptists” (meaning rebaptizers) and seen as a growing threat to the state order. Rejecting infant baptism, which was also tied with state citizenship, subverted state control, as did refusing military service. As a result, these reformers were targeted by authorities as a threat.

Persecution & Migration

In order to quell the growing movement, which also had representation in Germany and the Netherlands, state powers attempted various means of persecution, including imprisonment, fines, and exile. The threats escalated to torture and execution during the following century. So-called “Anabaptist hunters” were employed to pursue and capture Anabaptists. One estimate suggests that 4,000 Anabaptists may have been killed in these years (see Steven Nolt’s A History of the Amish, endnotes p. 341 Ch. 1 endnote #7). As a result, Anabaptists had to operate secretively, and also migrated to friendlier lands, such as the Alsace region in France, boosting pre-existing numbers of Anabapatists already living there.

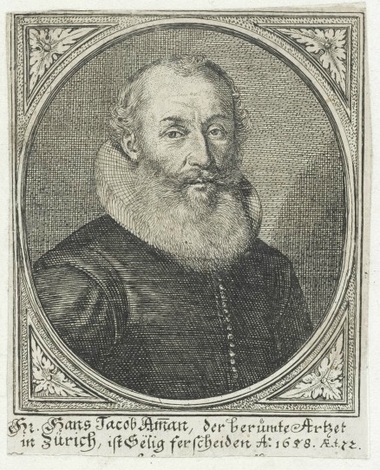

Jakob Ammann & The Amish

As the Anabaptist movement grew, internal conflict appeared due to disparate views among the Swiss faction. Anabaptist leader and convert to the faith Jakob Ammann was a hard-liner who emphasized the need for a few key practices: twice-yearly Communion rather than just once per year (to strengthen the church, as the congregation undergoes a period of self-reflection previous to communion) and the practice of social shunning of the openly sinful.

Jakob Ammann was responsible for twice-yearly baptisms and teh shunning of sinners.

Ammann felt that both of these practices would lead to a stronger church, though other leaders were not in agreement with Ammann’s reforms. In particular, Ammann came into conflict with a Swiss elder named Hans Reist over these issues, leading to a schism in 1693. Ammann’s harder line followers came to be known as Amish, and Anabaptists in other regions aligned on either side of the divide.

Migration in Europe and to North America

In ensuing years Amish migrated to different places in Europe, including Russia and the Netherlands. Others were drawn by the promise of Pennsylvania, William Penn’s colony known as a “holy experiment”, attractive to minorities for its religious tolerance.

It’s not known when exactly the first Amish journeyed to North America, but the first sizeable group, of 21 Amish families, left in 1737 for Pennsylvania. Others followed, construing the “first wave” of Amish emigration. These Amish, about 500 in total, settled in eastern Pennsylvania. A later second wave of around 3,000 settled in the Midwest, Ontario, and other states.

The Old Order begins

The first wave of Amish traveled from Europe to Pennsylvania in 1737.

In America, Amish prospered through the 19th century in a number of locations, including Illinois, Iowa, and Pennsylvania. At the same time, progressive religious forces threatened the traditional Amish identity. Numerous Amish congregations joined “higher” church movements, accepting greater levels of technology, gradually leaving behind traditional plain lifestyles, and adopting beliefs and practices influenced by mainstream religious movements.

Yet a conservative faction remained within the Amish, coalescing into the “Old Order” in the latter 19th century. A majority of Amish had taken progressive paths, so that by the year 1900, there were only about 5,000 Old Order Amish.

The 20th Century and Beyond

The story since then has been one of impressive growth, as Amish, with their high birth rate and retention, have reached a population of roughly 300,000 as of 2015. The Amish have also shown themselves willing to migrate within North America, as they currently have approximately 500 different communities in 30 states and Canada.

Over the 20th century Amish have faced conflicts in America, over issues including military service, schooling, raw milk sales, the Slow Moving Vehicle triangle, Social Security, child labor, and others. In most cases Amish have reached resolutions with government, with a number of religiously-based exemptions granted the Amish and related groups. Another notable development in the 20th century was the rise of small Amish business as a viable alternative to agriculture. This has proven attractive to Amish in many communities, especially in the face of increasingly expensive and scarce land in their traditional settlements.

The Future?

Despite constant pressure to change, and failed attempts outside North America, the future of the Amish is as assured as a well-sown harvest.

The Amish future in North America continues to look bright. Despite a handful of 20th-century settlement attempts outside of the US and Canada, today the Amish are found only in those two countries. Pressures on the Amish remain, including economic concerns as well as the allure of technology.

In contrast to the depiction of a people frozen in time, the Amish in fact change in various ways over time. Yet despite gradual change, they have preserved an Old Order identity by holding fast to key elements of their culture, such as Plain clothing, German dialect, and horse-and-buggy travel. Dating back to their earliest years in Europe, the Amish have proven themselves both resilient and able to change as they continue to pursue their heavenly goal as pilgrims “in the world, but not of it.”

By Erik Wesner, author of Success Made Simple: An Inside Look at Why Amish Businesses Thrive, and editor of the Amish America website. Steven Nolt’s A History of the Amish was used to prepare this article.